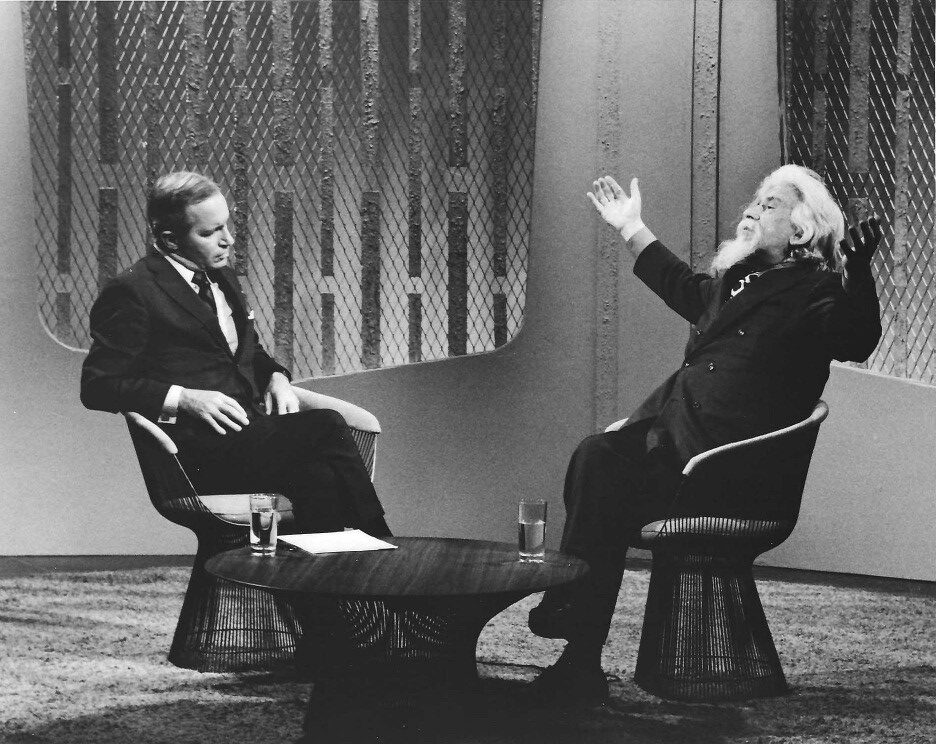

Heschel with ABC’s Frank Reynolds

Originally broadcast on the television program Directions on ABC on November 21, 1971. The conversation was about faith and spirituality in the modern world.

Originally broadcast on the television program Directions on ABC on November 21, 1971. The conversation was about faith and spirituality in the modern world.