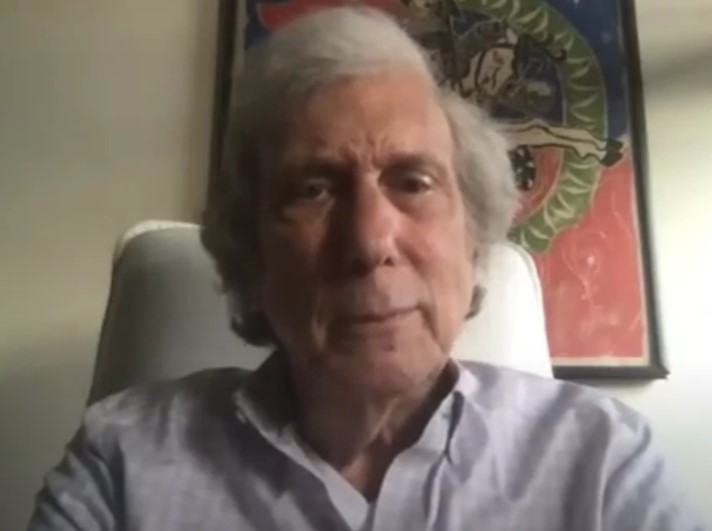

Dr. Arnold Eisen

I value Heschel's teaching that we are not all prophets but there should be something of the prophet in every one of us.

Chancellor Emeritus and Professor of Jewish Thought, JTS

New York, New York

A Jewish Perspective

I first encountered Heschel as a teenager. My Conservative synagogue in Philadelphia had an assistant rabbi named Nahum Waldman, who had the brilliant idea of taking the teens out of services and forming a discussion group about modern Jewish thought. I met Heschel, Kaplan, and Buber with a group of other teenagers. I concluded that the rabbi must have been as bored with services as we were. I often tell the story, which has a mythic air to it, that I opened God in Search of Man, where Heschel says, “Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid” – and was convinced that he had must have been to my synagogue.

Several years later, I was a reporter for the Daily Pennsylvanian when Heschel came to speak at Penn. I covered the story, and I screwed up my courage, which was an effort because I was very shy, and asked if I could interview him in New York. Months after I wrote about his speech at Penn, I drove up to New York, and knocked on the door of Heschel’s office at JTS. I will never forget the room. It was a tiny office that was full of books–not just on the shelves but piled high on the floor. There was barely room for our chairs. I spent an hour and three quarters with him and wrote up the story, which appeared in the Daily Pennsylvanian feature magazine.

This interview changed my life. Heschel realized quickly that I had personal questions that I needed to ask, and he met me where I was and spoke to me from the heart. I walked into this meeting needing Heschel to prove to me that Jewish life and the life of the mind were worthwhile: that ideas matter; Judaism matters; that religion can make a difference in the world. By the time I walked out of his office, I had no doubt about these things.

I try to be there for students when they are talking to me in my office, as Heschel was for me. Martin Buber wrote somewhere that you have to not only answer the questions that are asked by the person before you, you have to answer the questions that are not asked. Heschel certainly did that when I sat before him.

In the interview I asked: where did you get the chutzpah to say that religion declined because it became irrelevant, oppressive, insipid and dull? You don’t exclude Judaism from this generalization, so you’re saying that the religion that many Jews are practicing is irrelevant. Where do you get the authority to say that? And first he tried to duck the question– he said that some people like vanilla ice cream, some people like chocolate ice cream. I replied, Rabbi Heschel, we’re not talking about ice cream. We’re talking about people’s lives. And then he said: President Nixon thinks the war in Vietnam is justified, and I think it’s evil. Then he said something close to the following, which I must confess I didn’t quote it exactly like this in the Daily Pennsylvanian piece, but this is what I remember: “I am the heir to a great religious tradition. And as such it is not only my right, it is my duty to speak in the name of that tradition as best I can, knowing that other people will speak differently.”

That has meant everything to me. Heschel’s stance on civil rights was popular, but his leadership in the anti-war movement was extremely controversial. He wasn’t just saying, “on balance, I have concluded that the war is wrong.” Heschel said the war was evil.

When I became Chancellor Elect of JTS, we had to make a decision about the ordination of gay and lesbian clergy, following the historic halakhic ruling by the Law Committee of Conservative Judaism. I Heschel’s words in my mind: I’m an heir to this religious tradition that I love. And as such I had not only the right, but the duty to speak in its name as best I could Heschel gave me the justification that I needed for taking on this enormous issue. I resist answering questions about “what would Rabbi Heschel do or say in our day about this or that matter?” Because we can’t know what a person who passed away decades ago would do today. But Rabbi Wolfe Kelman said something to me that was very wise. He said that Heschel sometimes opened doors for people that he himself did not walk through.

I belong to the generation of people who tried to follow him, were inspired by his words and tried to take them further.

My academic career has focused on understanding modern Judaism in terms of the challenges Jews faced and the responses major thinkers and “Jews in the pews” have made to those challenges. I chose a historical perspective as opposed to a sociological one because I didn’t want to be an outsider to my own tradition, looking at figures like Heschel in terms that come from secular disciplines. The texts and thinkers I study are of personal importance to me. Abraham Joshua Heschel and Mordecai Kaplan often asked versions of the same questions that concern me by day and keep me up at night. Heschel influenced my career choice. And he changed my life. Here was a man of great learning and immense piety, the author of many beautiful books who was also and an activist who put his learning into practice in pursuit of justice.

You ask: What of Herschel does not live in me? I will never be as learned or pious or courageous as he was. I value Heschel’s teaching that we are not all prophets but there should be something of the prophet in every one of us. Heschel taught me that we’re not just here to sit in shul or in the study hall. There is work to be done and we must be active doing that work in the world. Torah must lead to action. Heschel wanted us to take God seriously to take the study of Torah seriously and to take action in the world seriously. I got that from him at the age of twenty and it has remained fundamental to who I am and try to be. That’s an incredible gift for one person to give to another. I will be indebted to this man for as long as I live.

Connected Texts:

“Heschel Urges Festivity and Sense of Awe in World of ‘Tedium, Humdrum Inevitability.” The Daily Pennsylvanian. (2/26/1971).

“Miracles and a Shrug of the Shoulders.” 34th Street. (10/7/1971)