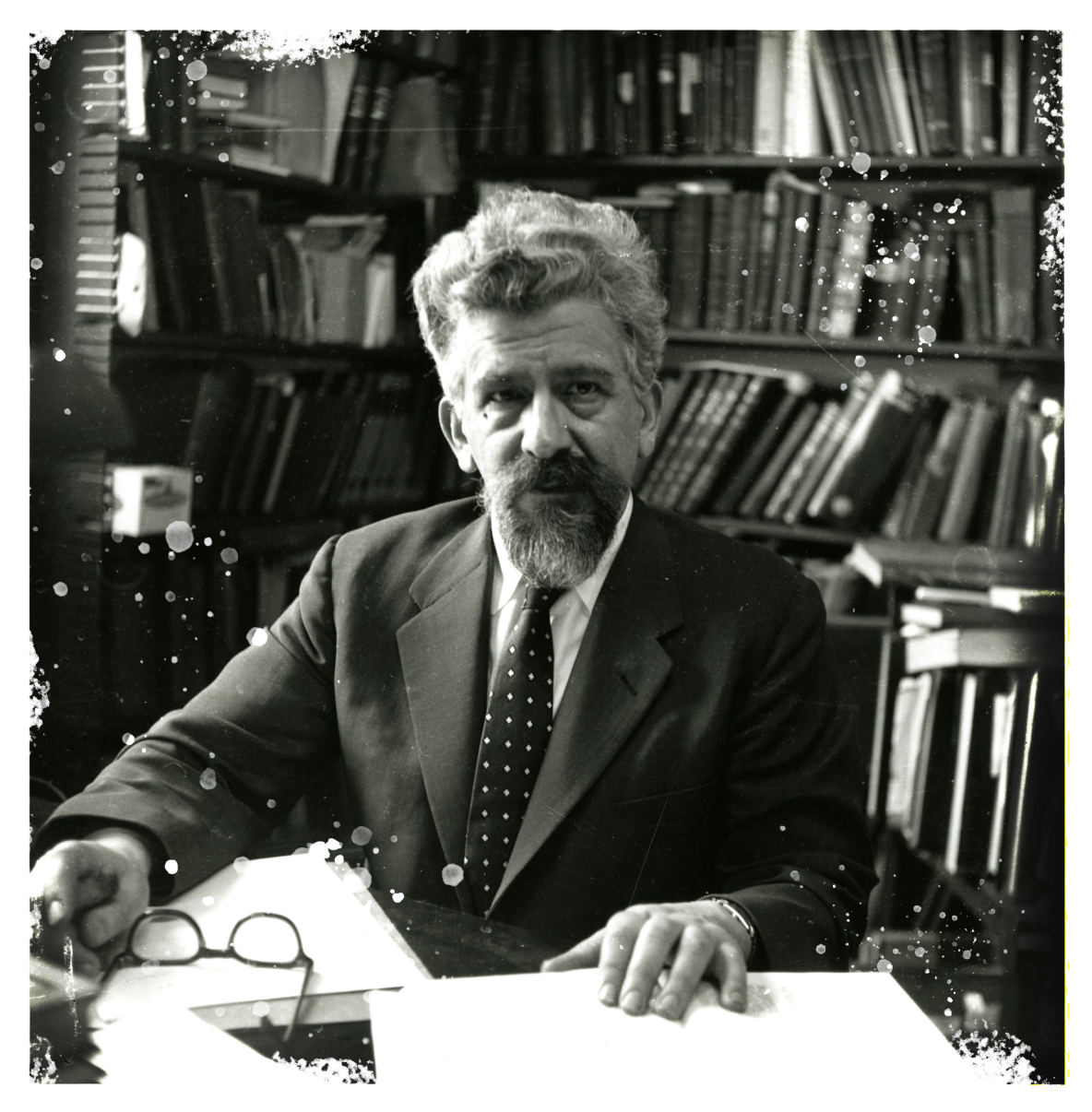

Heschel's Life & Work

"Heschel’s genius embraced a number of fields."

"He wrote seminal works on the Bible, the Talmud, medieval thought, philosophy, theology, Hasidism, and contemporary moral problems. He was a theologian, a poet, a mystic, a social reformer, and a historian. Indeed, the best of the whole tradition of Israel, its way of thought and life, found unique synthesis in him. Rooted in the most authentic sources of Israel's faith, Heschel's audience reached beyond creedal boundaries. He was easily the most respected Jewish voice for Protestants and Catholics: his friendship with Reinold Niebuhr was memorable and his crucial role at Vatican II has yet to be described ... The years since his passing, far from dimming his person, cast in even brighter relief the unique role he played on the contemporary scene, a role no Jew, or Gentile for that matter has since filled." —Samuel H. Dresner (“Introduction,” I Asked for Wonder: A Spiritual Anthology, 1983)

Early Life

1907–1923

January 11, 1907: Abraham Joshua Heschel was born in Warsaw. He was the youngest of six children of Moshe Mordecai Heschel and Reizel Perlow Heschel. His six siblings were Sarah, Dvora Miriam, Esther Sima, Gittel, and Jacob. He was part of a Hassidic dynasty, stemming from a long line of rabbis. From Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity:

I was very fortunate in having lived as a child and young boy in an environment where there were many people that I could revere, people concerned with the problems of inner life, of spirituality and integrity. People who have shown great compassion and understanding for other people.

1916: His father died of the flu.

Early Learning

1910s–1927

He was tutored by a Gerrer Hasid who introduced him to the thought of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk; Heschel reflected on the Kotzker Rebbe in his book A Passion for the Truth.

His friends from childhood included Zalman Shazar, who became president of Israel, and Yiddish writer Yechiel Hoffer. Hoffer wrote about Heschel in his semi-autobiographical novels.

1922/23: Heschel published his first articles in the Warsaw rabbinical publication Sha’are Torah.

1925: He moved to Vilna to study at the Mathematical-Natural Science Gymnasium, where he probably specialized in languages and literature.

July 24, 1927: Heschel completed his examinations at the Gymnasium in Vilna.

Higher Education in Germany

1929–1938

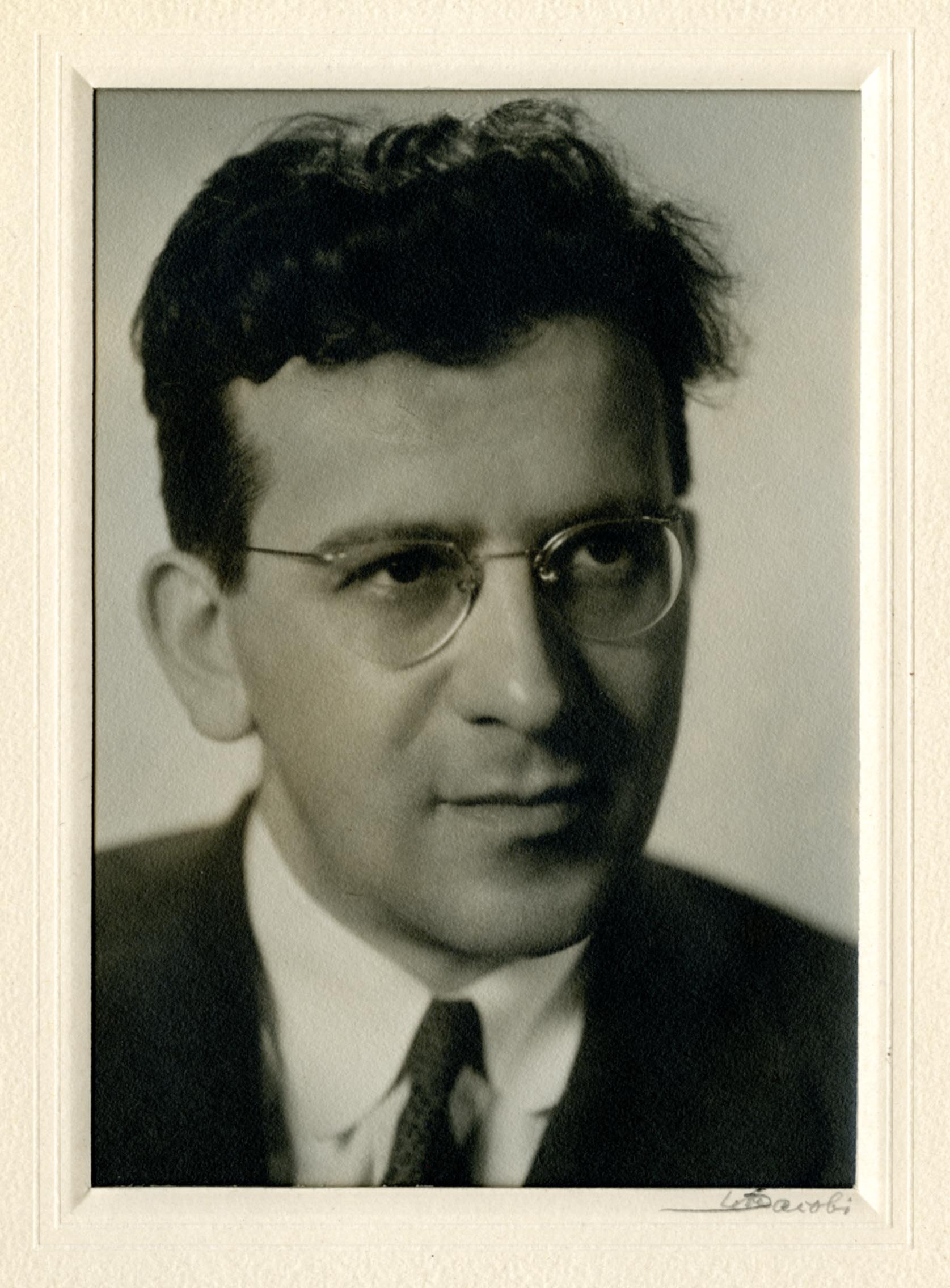

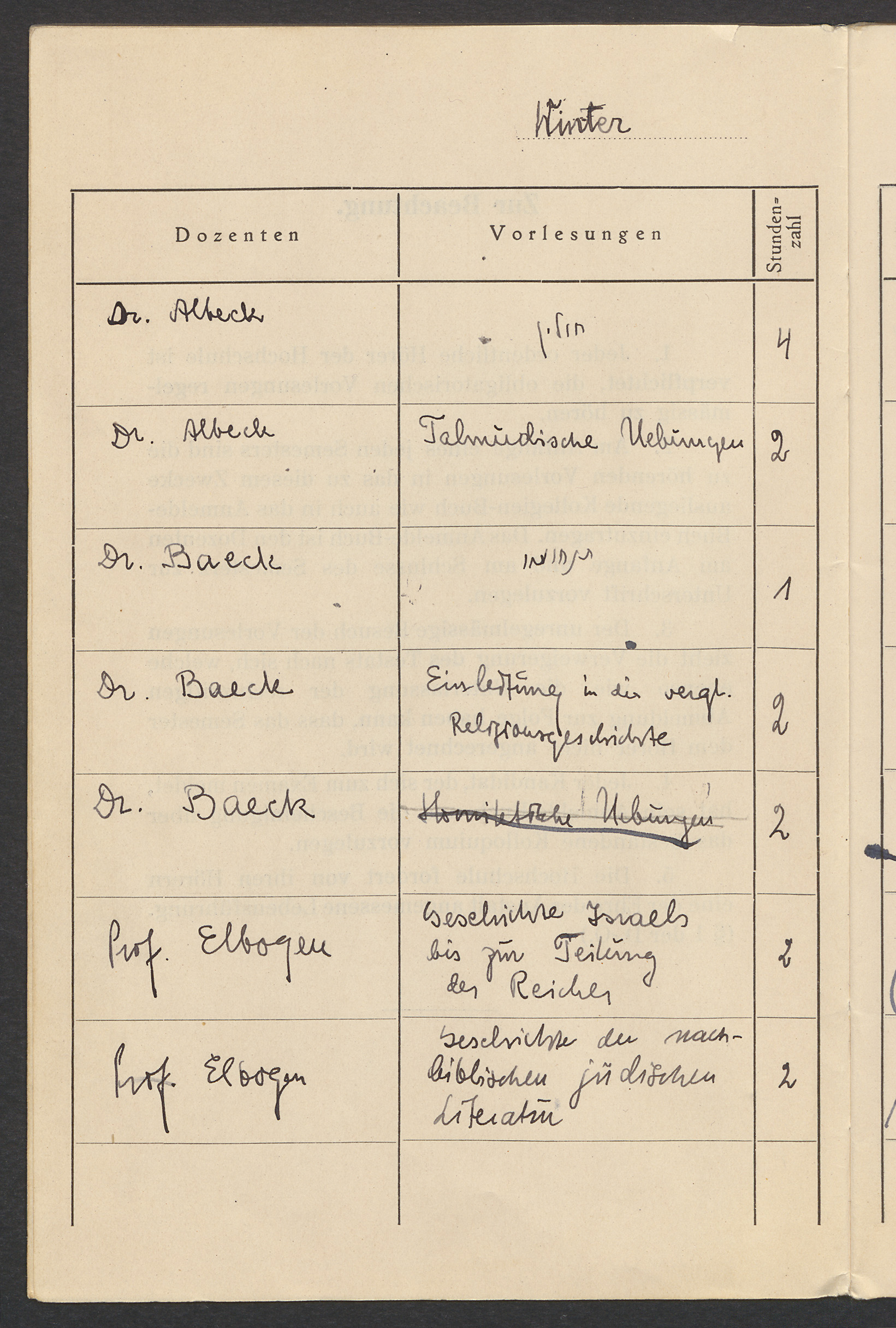

Fall 1927: Heschel arrived in Berlin to study philosophy with secondary work in art history and Semitic philology at Friedrich Wilhelm Universitat, now Humboldt University.

April 29, 1929: He passed his matriculation exams. While working toward his doctorate, Heschel was also ordained by the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, where he was trained in modern scientific study of Jewish texts and history. While receiving this education, he maintained his connection to the Orthodox seminary across the street.

January 30, 1933: Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Less than two months later, he was granted the power to act without parliamentary consent. Heschel’s life as a Polish Jew was profoundly impacted. In the next years, he experienced both professional and personal challenges.

1933: He published a volume of Yiddish poetry Der Shem Hamefoyrosh: Mentsch (The Explicit Name: Man), which he dedicated to his father. The book was highly regarded and Heschel received a letter from leading Yiddish poet Chaim Nachman Bialik about this collection.

He wrote his dissertation, Das prophetische Bewuβstein (Prophetic Consciousness). This work was later adapted and expanded by Heschel into his 1962 book in English The Prophets.

April 1933: He published the Yiddish poem “A Day of Hatred” anonymously in a Polish newspaper following book burnings.

December 1935: He was awarded his diploma three years after he completed his work.

1935: He published a book on Maimonides in German, which highlighted Maimonides’s personal struggles and spiritual life.

1936: His dissertation was published in German under the title Die Prophetie. In order to fulfill the conditions for his degree, this work had to be published. Like all elements of German society, publishing was under Nazi control, making publication incredibly challenging. It was finally distributed by the Polish Academy of Sciences (Krakow) with funding from a German publishing house (Erich Reiss Publishing, Berlin). Without his PhD, it would have been harder to immigrate.

March 1938: Heschel delivered a lecture to a conference of Quaker leaders in Frankfurt-am-Main entitled “The Meaning of This Hour.” Quaker Pastor Rudolf Schlosser became a friend. Schlosser and the Quaker community helped Heschel with his visa process, writing letters of support to the US consulate. Heschel’s imperative to not be a bystander came out of this period when he saw so many Christian people stand by as Jews were being targeted. From “The Meaning of This Hour”:

There can be no neutrality. Either we are ministers of the sacred or slaves of evil.

Escape

1938–1939

I am a brand plucked from the fire, in which my people was burned to death.

October 1938: Heschel was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to Poland. He had one hour to pack two suitcases. He was held overnight in a cell before being crowded onto train to Warsaw for a hellacious three-day journey in which he had to stand the whole time. The people on the train were denied entry into Poland and there was not enough food to sustain the overcrowded passengers. Heschel’s family secured his release.

He spent the next 10 months lecturing at the Warsaw Institute for Jewish Studies.

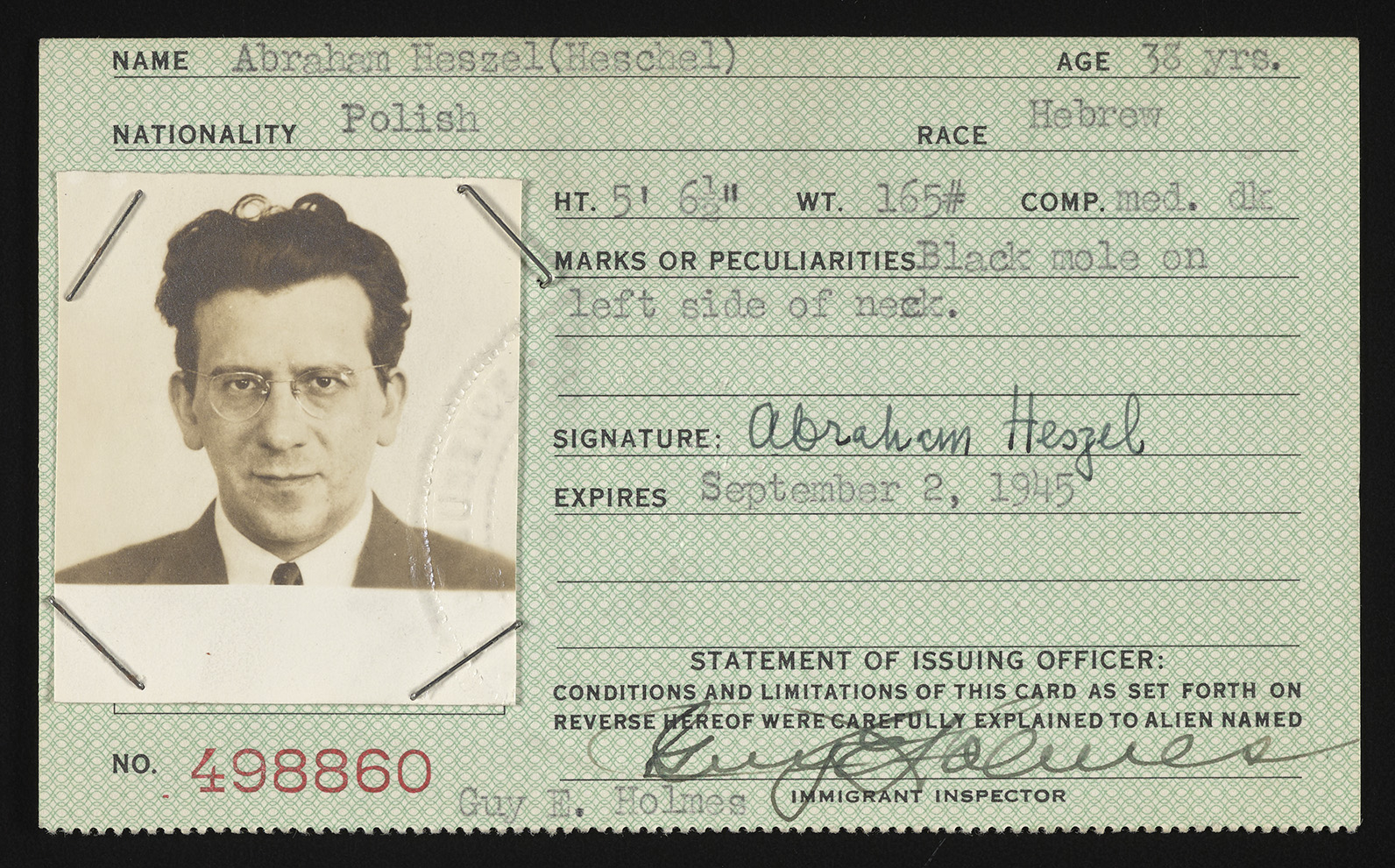

July 1939: Six weeks before the German invasion of Poland, Heschel left Poland for London. This was arranged by Julian Morgenstern from Hebrew Union College (HUC) and Alexander Guttman, another one of the 16 individuals who came to the United States through the efforts of HUC. Guttman rewrote Heschel’s ordination certificate to meet American visa requirements. Heschel was selected on the strength of his publications and assisted by the fact that he was unmarried. It was considerably easier to get a visa for one person rather than a family.

September 1939: Morgenstern sent Heschel an official letter of appointment, which was received in late October.

It gives me great pleasure to extend to you, in the name of the Hebrew Union College, located in Cincinnati, Ohio, a call as a teaching member of the Faculty, with the title of Instructor in Bible, for an indeterminate period, at a salary of $1,500.00 for the first year … I am sending a copy of this letter to the American Consul in Dublin by this same mail. I would urge therefore that you contact the Consul in order to expedite as much as possible your departure for the United States.

Beginnings in the United States

1940–1946

I have just arrived in New York! Barukh Hashem [Thank God]!

—letter to Julian Morganstern

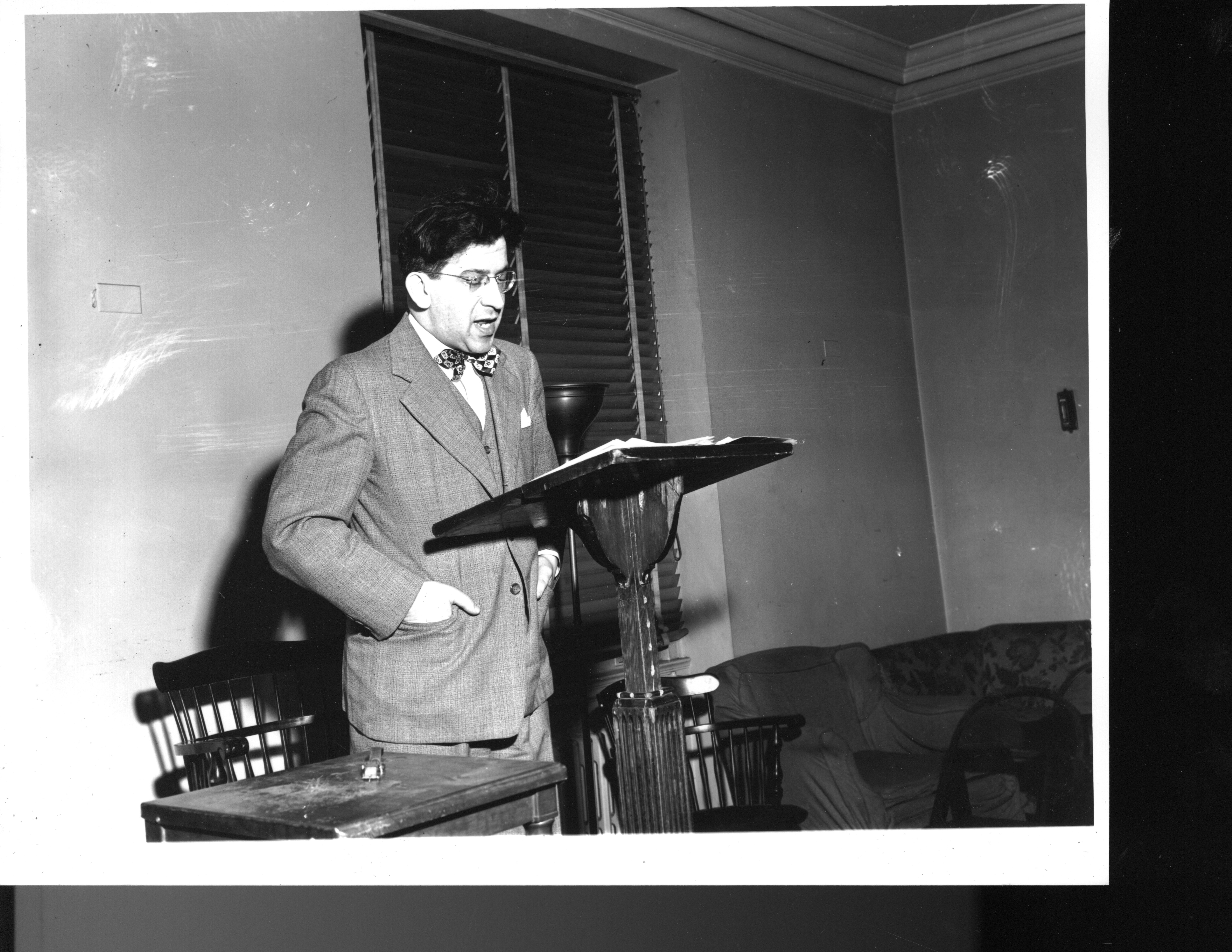

March 1940: Heschel arrived in the United States.

He served on the faculty of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati for five years. While there, he began publishing scholarly philosophical articles in English. He also met the woman who would become his wife, Sylvia Straus. A Cleveland native, she was in Cincinnati to study with concert pianist Severin Eisenberger.

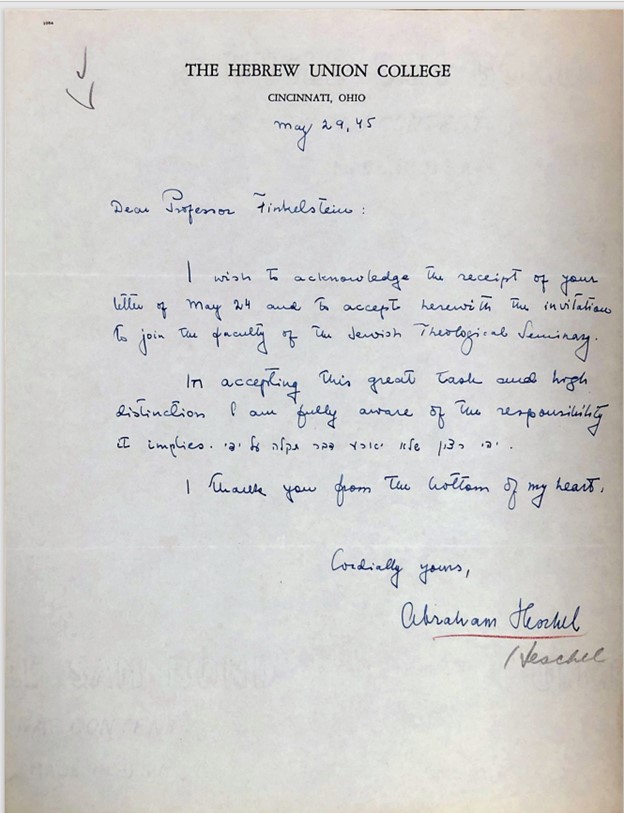

May 29, 1945: Heschel accepted a position with The Jewish Theological Seminary as professor of Jewish ethics and mysticism.

December 10, 1946: He married Sylvia Straus in Los Angeles.

Building a Life of Meaning

1946–1972

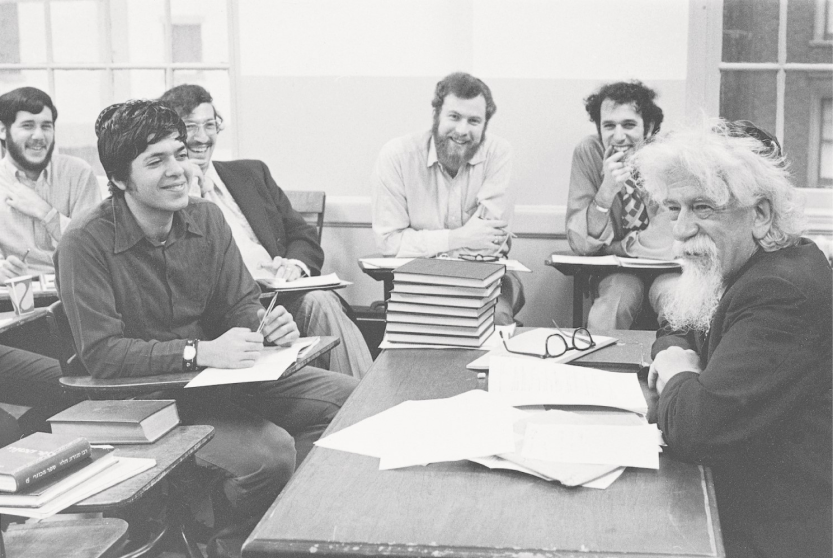

Heschel began teaching at The Jewish Theological Seminary, which trains Conservative rabbis.

Heschel’s move to New York marked a period of incredible productivity. In the early 1950s, he published four of his best-known works.

-

- Man Is Not Alone (1951)

- The Sabbath (1951)

- Man’s Quest for God (1954)

- God in Search of Man (1955)

May 15, 1956: Daughter Susannah Heschel is born.

January 5, 1959: Heschel was promoted to full professor.

1962: Published The Prophets, which began as a translation of his PhD dissertation but was expanded into a two-volume edition.

“Prophecy is the voice that God has lent to the silent agony, a voice to the plundered poor, to the profane riches of the world. It is a form of living, a crossing point of God and man. God is raging in the prophet’s words.”

1962: He published volume one of Torah Min Hashamayim in Hebrew. The second volume was released in 1965, and a third volume was published posthumously. The books were translated in 2005 and published under the title Heavenly Torah.

1965–1966: Heschel became the Harry Emerson Fosdick Visiting Professor at Union Theological Seminary, across the street from JTS.

1967: After the Six Day War, Heschel flew to Israel; he later wrote Israel: An Echo of Eternity (1969) about the religious significance of the Jewish State.

December 1972: Heschel recorded an interview with Carl Stern for The Eternal Light, an NBC show produced in partnership with JTS. This interview was broadcast posthumously.

Nostra Aetate–Building Bridges

1961–1965

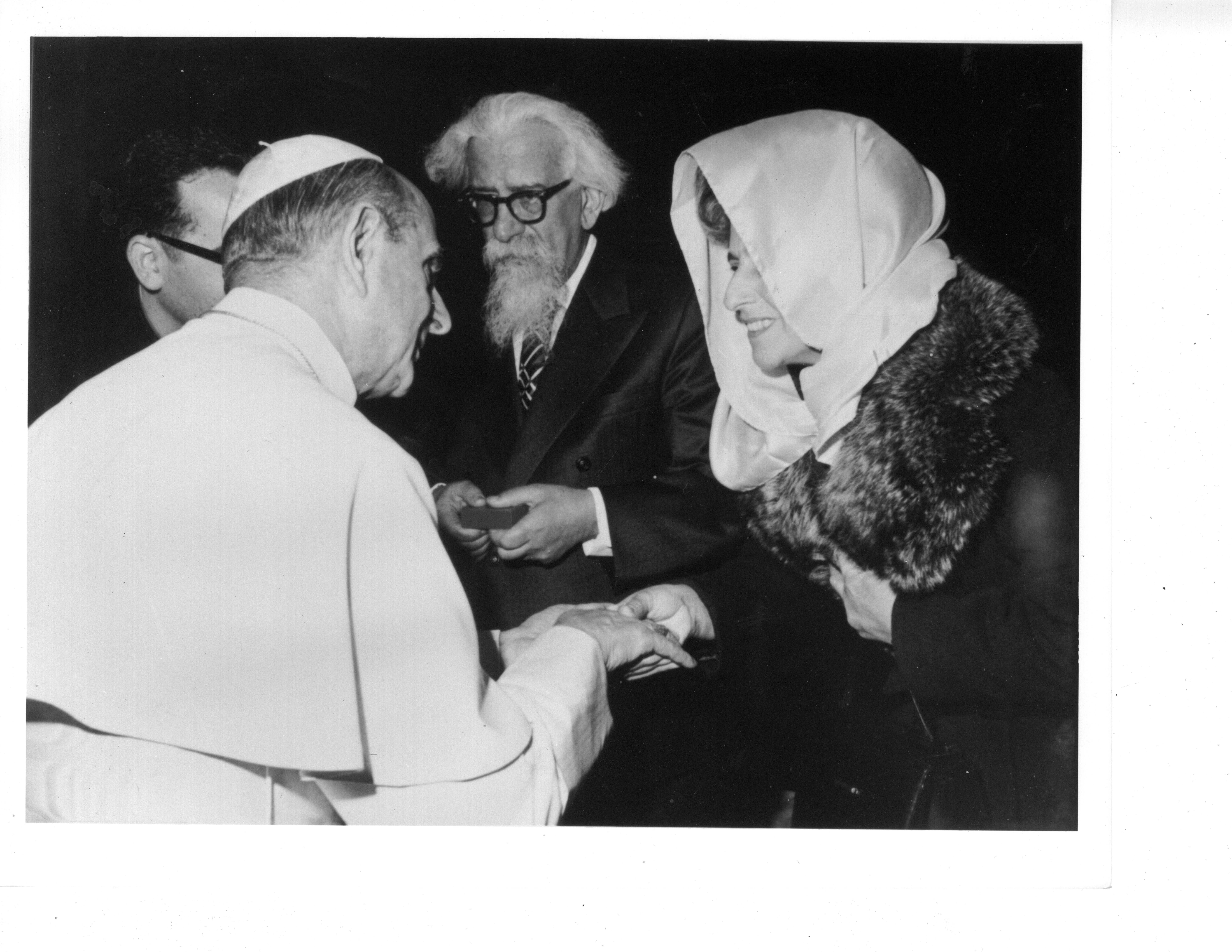

November 1961: Heschel began meeting with Cardinal Augustin Bea as part of the process to revise Catholic theology toward other religions. Heschel was selected by the American Jewish Committee to represent the Jewish position in these talks. These meetings led to Nostra Aetate, the landmark publication that fundamentally shifted the way that the Catholic faith understood its ties to Judaism and its relationship with Jewish people. Throughout these meetings, Heschel pushed Bea and others to change the Catholic presentation of Jewish responsibility in the trial and crucifixion of Jesus, and to end the Catholic emphasis on converting Jews.

October 28, 1965: Pope Paul VI issues the historic Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, otherwise known as Nostra Aetate, the landmark document that changed the relationship between Catholics and Jews.

Activism

1960s–1970s

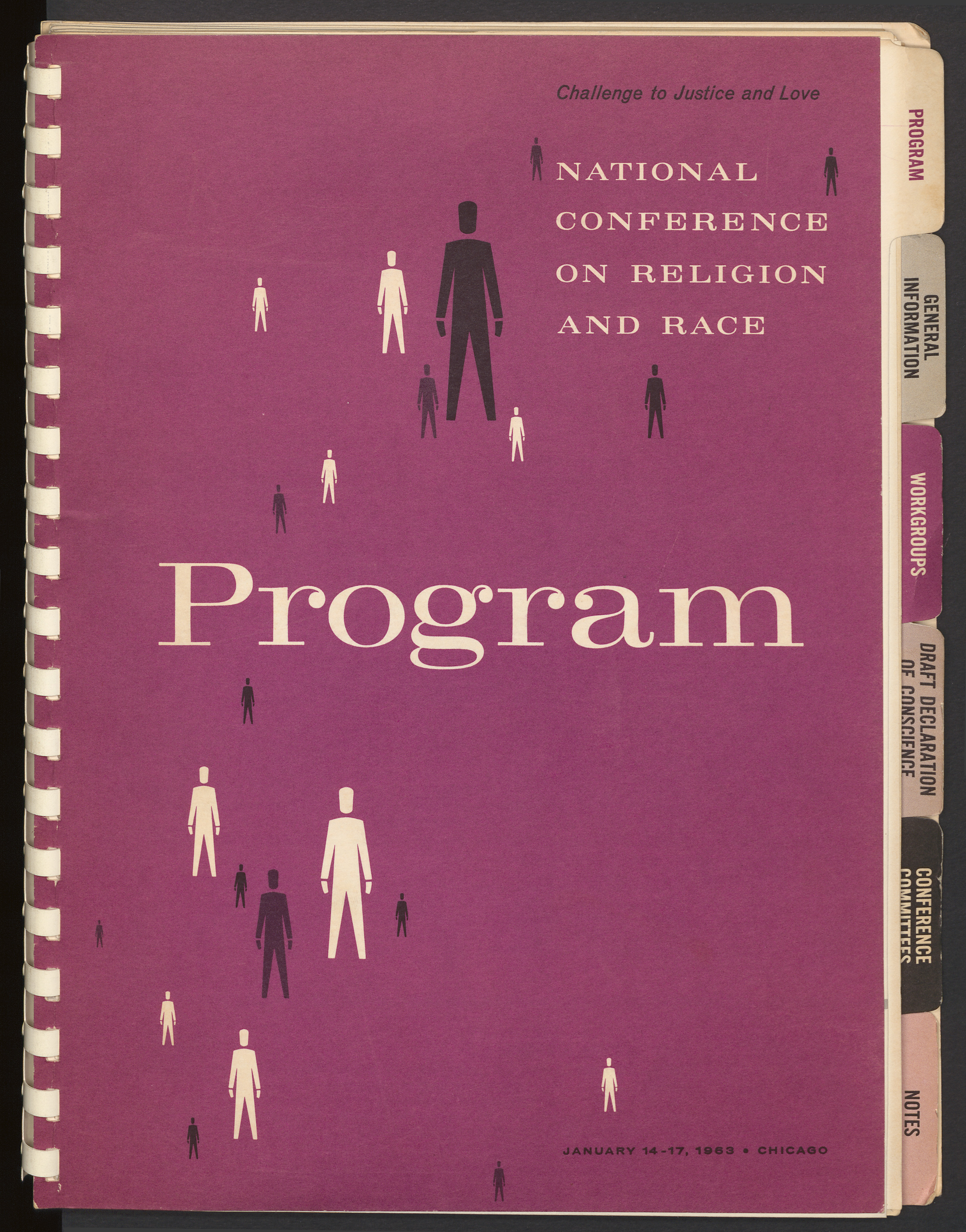

January 14, 1963: Heschel met Martin Luther King, Jr., at the Conference on Religion and Race, where he delivered a speech entitled “Religion and Race”:

Few of us seem to realize how insidious, how radical, how universal an evil racism is. Few of us realize that racism is man’s gravest threat to man, the maximum of hatred for a minimum of reason, the maximum of cruelty for a minimum of thinking.

June 17, 1963: President Kennedy convened a group of religious leaders to discuss racial discrimination. The day before the meeting, Heschel sent this telegram to RSVP:

I look forward to privilege of being present at meeting tomorrow. Likelihood exists that Negro problem will be like the weather. Everybody talks about it but nobody does anything about it. Please demand of religious leaders personal involvement not just solemn declaration. We forfeit the right to worship God as long as we continue to humiliate Negroes. Church synagogue have failed. They must repent. Ask of religious leaders to call for national repentance and personal sacrifice. Let religious leaders donate one month’s salary toward fund for Negro housing and education. I propose that you Mr. President declare state of moral emergency. A Marshall plan for aid to Negroes is becoming a necessity. The hour calls for moral grandeur and spiritual audacity.

March 21, 1965: Heschel marched with Martin Luther King and other religious leaders in Selma, Alabama. This was part of a larger series of marches that responded to the brutal events that unfolded in Selma on March 7 which became known as Bloody Sunday. Heschel read Psalm 27.

For many of us the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.

1965: Founded Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam (CALCAV) with John Bennett and Richard Neuhaus.

April 4, 1967: Martin Luther King gave his first speech against Vietnam at Riverside Church. Heschel had actively encouraged him to make a statement, and he introduced King that evening.

February 6, 1968: Under the auspices of CALCAV, Heschel, King, and 2,500 others marched to Arlington Cemetery to protest the war.

Heschel was an active participant in both the antiwar movement and the Civil Rights Movement until his death in 1972.

May His Memory Be for a Blessing

1972–

December 23, 1972 (18th of Tevet 5733): Heschel died on Shabbat at the age of 65. The academic journals of Catholicism and Conservative Judaism each dedicated an entire edition to his memory.

1972: Abraham Joshua Heschel Day School was founded in Los Angeles.

The school’s namesake, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, was not only a brilliant philosopher and influential teacher, but he also embodied our core values: tradition, character, and community. His varied interests in religious pluralism, human dignity, civil rights, personal fulfillment, Israel, education, mitzvot, and service speak directly to the pillars on which we were founded.

1979: United Synagogue Youth (USY) named their selective honor society after Heschel.

1983: The creation of the Abraham Joshua Heschel School was spearheaded by founder Peter Geffen in 1981. Together with educators and lay people from a broad spectrum of the Jewish community, they worked to project a vision for a pluralistic Jewish school. The school opened its doors to 28 students in the fall of 1983.

1990s: Heschel Center for Sustainability was founded in Israel.

1992: JTS Chancellor Ismar Schorsch and Dr. Cornel West record a conversation entitled, “Abraham Joshua Heschel Remembered”; listen to Part 1 and Part 2

1996: The Heschel School in Toronto was established.

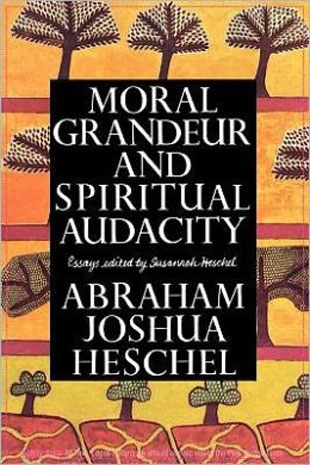

1996: Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, a collection of Heschel’s essays, was published by daughter, Dr. Susanna Heschel, and wife, Sylvia Heschel.

2005: Heavenly Torah: As Refracted Through the Generations was published. This book is the English translation of Heschel’s 1962 multi-volume work Torah Min Hashamayim.

December 2014: The Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem hosted the International Conference on Abraham Joshua Heschel: Philosophy and a Path Tested by Time

2020s: The Heschel Center began its activities at the Catholic University of Lublin with a focus on interreligious dialogue between Catholics and Jews

November 29, 2022: The International Conference on Abraham Joshua Heschel took place. It was sponsored by The Cardinal Bea Centre for Jewish Studies, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the Latin American Rabbinical Seminary and the Abarbanel Institute, both based in Buenos Aires.