Rabbi Martin Cohen, PhD

That book [The Prophets]—almost more than any other—set me on the course that eventually became my life.

Shelter Rock Jewish Center

Roslyn, New York

A Jewish Perspective

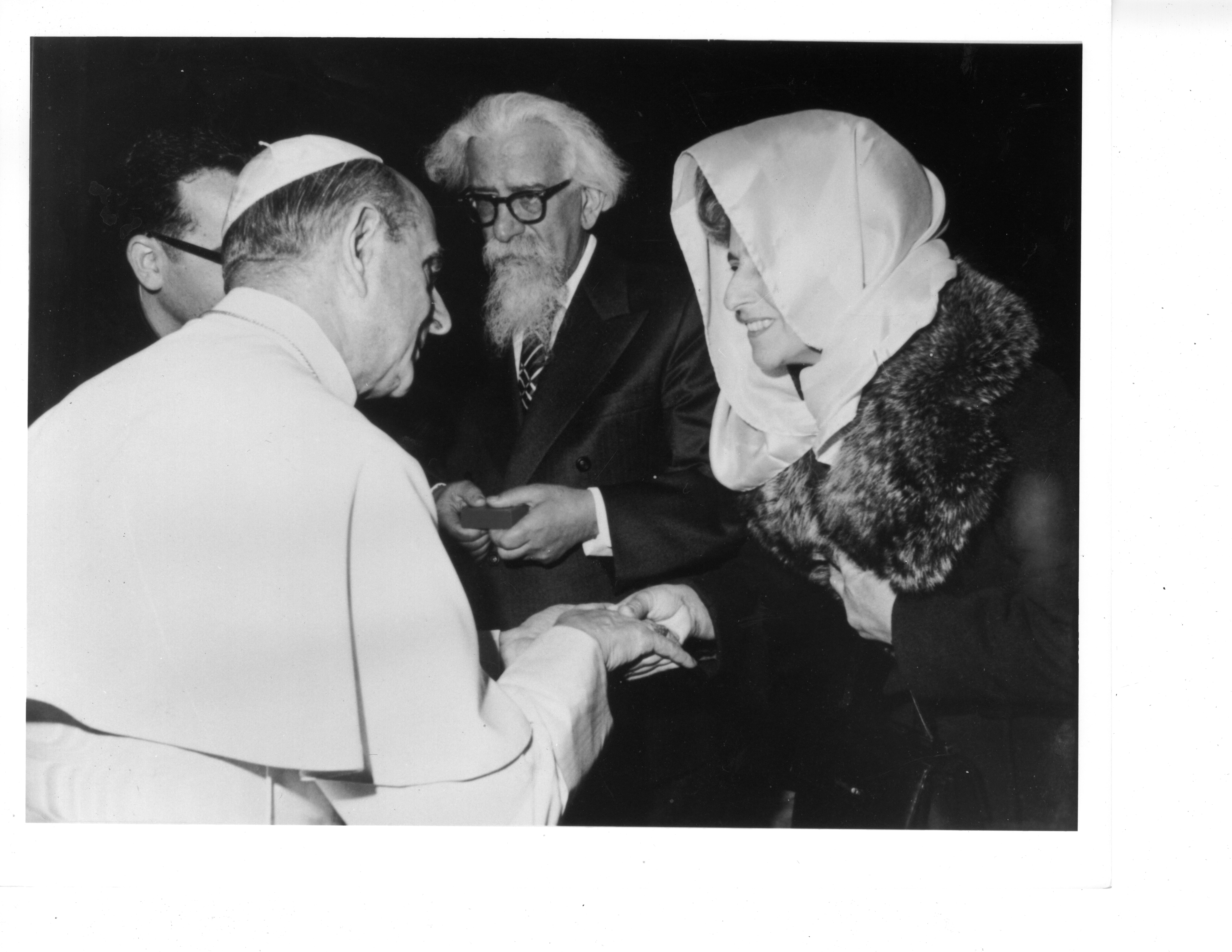

I never met Professor Heschel in person. In fact, we just missed each other: he died in the winter of 1972 and I only began my studies at JTS in the fall of 1974. But even so I can say that he was responsible both for my choice of JTS for rabbinical school and for my choice of the rabbinate, and particularly the congregational rabbinate, as my life’s profession.

As I moved closer to organized Jewish life and to Jewish observance, I was all over the map: I worked at one of the UAHC summer camps and taught in a Reform Religious School, but on Shabbat I davened in an super-traditional shtibl. I wore a tallis koton under my shirt, but walked around bareheaded in the street. In a strange inversion of my parents’ custom, I kept strictly kosher only outside of the house. I owned a pair of bar-mitzvah tefillin (the purchase was, as I recall, requisite), but I had no idea how to adjust the head strap to make it fit my grownup-sized head. My rabbinic models were both Conservative rabbis: Rabbi Max Arzt and Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser, both now of blessed memory. But I was still smarting from being refused admission to the Hebrew high school in the synagogue I thought of as my own because my parents weren’t actually members, just non-members who sent me to Hebrew school there, made my bar mitzvah there, and paid a fortune for non-member seats on the High Holidays. So I was the embodiment of the wandering Jew: at home everywhere and nowhere.

And then I discovered Heschel and things began to clarify. First, I came across God in Search of Man in a second-hand bookshop in North Adams, Massachusetts. I was confused (there were whole chapters I didn’t understand at all), but also intrigued. A few months later, I noticed a copy of Man’s Quest for God in, of all places, my barbershop on Queens Blvd. in Forest Hills. When I asked the barber why it was there among all the magazines, he told me that someone had left it there and not returned for it. I was free to take it if I wished. I did take it, and I read it through in a day or two. I had no idea at the time, but in retrospect I see myself being drawn forward in a specific direction. And then, in the fall of my sophomore year in college, I bought a copy of The Prophets, published for some reason in those days in two volumes. I was still reading the first volume when I saw in the paper one morning that its author had died the day before.

I didn’t attend the funeral. Why would I have? But Heschel’s death only made it seem more urgent that I read even more intently; since I was obviously not going to meet the man in person, all I could do was try to know the author through his work. Reading that book, Heschel’s The Prophets, was transformational for me. I had just begun to understand how the Tanakh was put together, which books went where, which were the earlier works and which the later. I was at the very beginning of my studies, and in every imaginable way. But here was a work that showed me—not told me or suggested to me, but showed me graphically and profoundly—just what it could mean to live a life immersed in the literary heritage of Israel. Heschel seemed to know these people—these ancient prophets whose words he appeared not only to know inside-out, but to be able to look through into the souls of their speakers. He wrote about Isaiah, about Amos, especially about Jeremiah (I thought) as though he knew them. Or, even more amazingly, as though he knew them intimately, as though he and they were—impossibly—friends.

More to the point was the God-talk in that book: Heschel was able to paint a portrait (an aniconic one, of course) of God using the chapters of the prophets’ visions and oracles as his paintbox. It wasn’t only God’s prophets that he appeared to know as contemporaries and intimates; it was the God they served whom Heschel seemed to know personally. And that concept of Friend God, as opposed to Judge God or Sovereign God, appealed mightily to me. I read the second volume (much more difficult, I thought, than the first). Then I read both books a second time. Eventually, I set them aside: I was a college sophomore and was drowning in my “real” reading assignments. Reading Heschel and, particularly, The Prophets, seemed to me at the time mere happenstance. But when I think about things after all these many years, I can see that some seed had been planted, that some germ of an idea had taken root somehow deep within. It took a while for that idea to make itself fully manifest to me (how that happened would be a different story), but that book—almost more than any other—set me on the course that eventually became my life.